The Making of a Synthetic World

Adam Hanieh

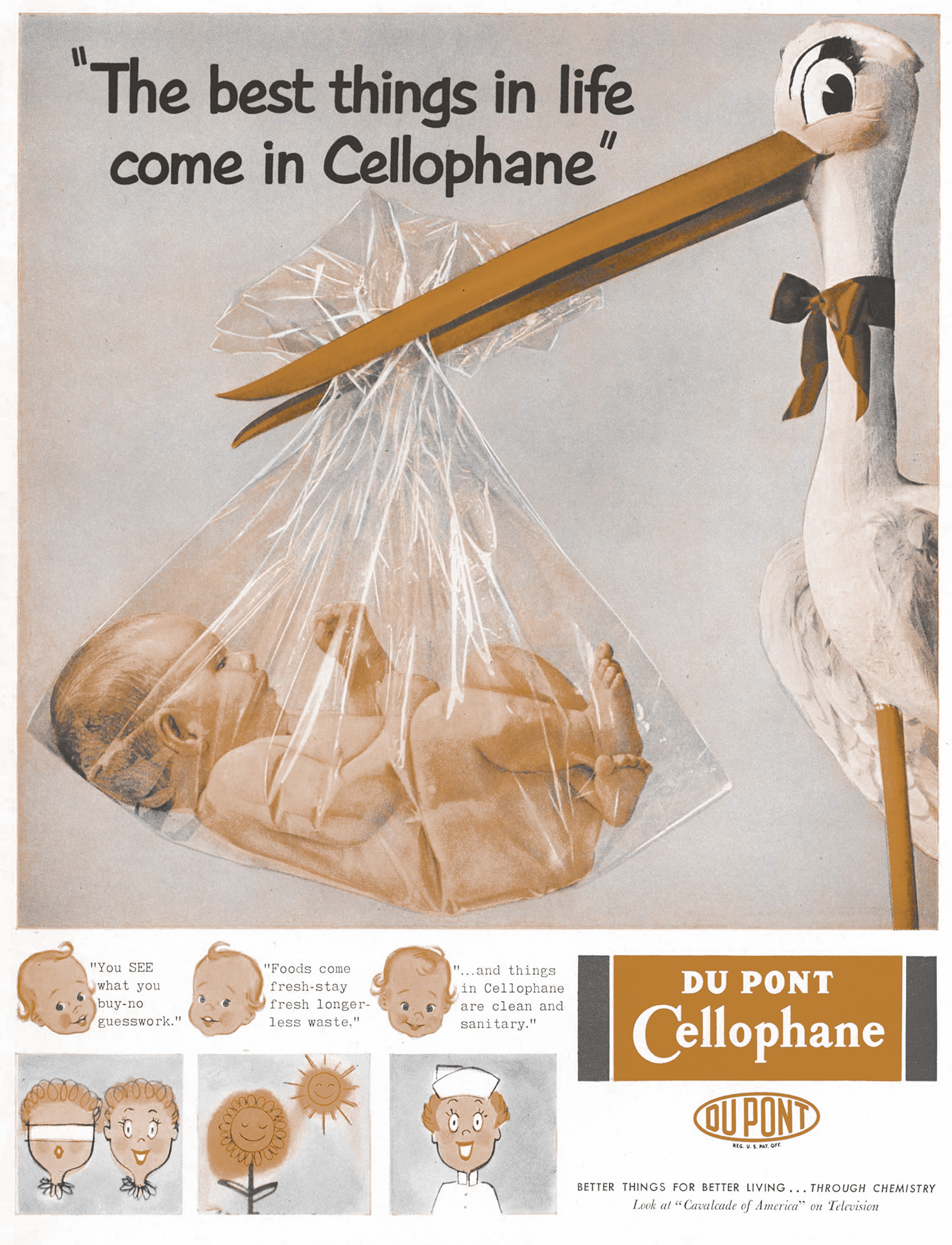

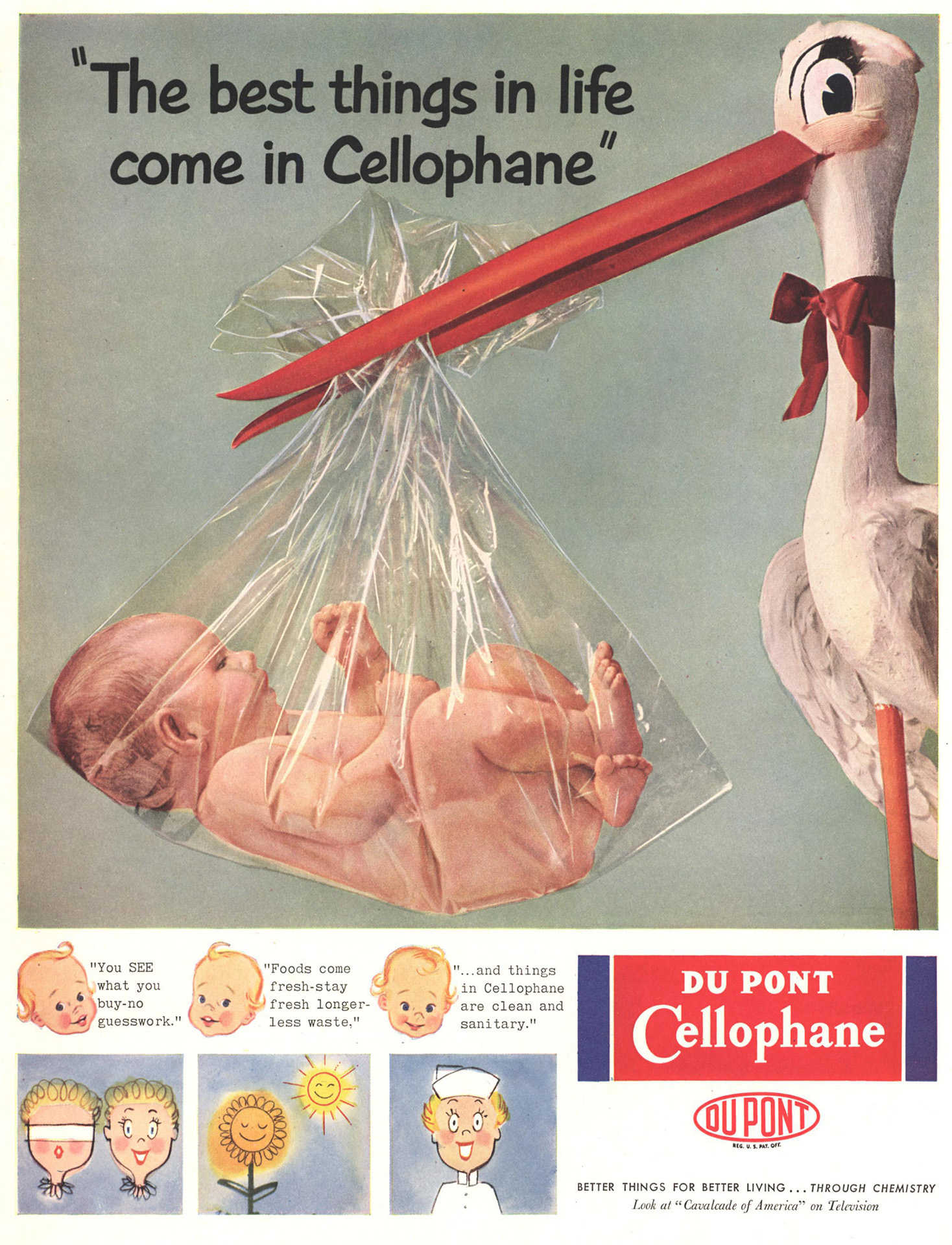

Advertisement for DuPont Cellophane c. 1955. © The Advertising Archives/Bridgeman Images.

Cover of Vance Packard, The Waste Makers (New York: Pelican, 1960).

In the decades immediately following World War II, the rapid spread of synthetic materials derived from petroleum colonized all aspects of everyday life. These new petrochemicals reshaped the cultural practices and material products associated with the “American Dream.” At its core, the petrochemical industry represented a qualitative shift in how we produce. The functional attributes of natural materials, such as wood, glass, paper, natural rubber, natural fertilizers, soaps, cotton, wool, and metals, would now be served by plastics, synthetic fibers, detergents, and other petroleum-based chemicals. This was the beginning—proclaimed a Fortune magazine headline in 1950—of the “Chemical Century.”“The Chemical Century,” Fortune 41, no. 3 (March 1950): 116–121.

As injection-molding machines were developed through the 1950s and 60s, plastics enabled the automated fabrication of cheaply reproducible components that transformed whole branches of industrial production. Akin to modern day alchemy, a bag of small pill-like thermoplastic pellets could be transformed into any simple commodity with the appropriate mold. Once a mold was set, there was little extra cost to manufacturing each item—not only dramatically reducing the need for labor but also encouraging enormous increases in commodity output.

As huge quantities of new and easily reproducible synthetic goods displaced natural materials, corporations were faced with the obstacles of limited market size and the restricted needs of the postwar consumer. Ever-accelerating quantities of waste, inbuilt obsolescence, and automated production became the hallmark of capitalist manufacture—a situation presciently narrated by Vance Packard in his 1960 classic, The Waste Makers. As Packard noted, the solution to this dilemma was closely connected to the emergence of another “new” industry: advertising, which aimed at inculcating the mass consumer “with plausible excuses for buying more of each product than might in earlier years have seemed rational or prudent.”Vance Packard, The Waste Makers (New York: David McKay, 1960), 29. Wants became needs, with the malleability of desire driving an ever-present disposability—a fickleness ultimately aimed at speeding up the circulation of commodities. But branding needed a “skin,” and advertisers turned, once again, to plastics for a solution. The pervasive supply of cheap and pliable petrochemicals enabled a vast expansion in packaging and labeling, which soon came to encase all consumer goods. Packaging quickly became the largest end-use for plastics, now making up more than one-third of the current demand for global plastics.

This narrative points to the real problem with fossil fuels. Having become so accustomed to thinking about oil and gas as primarily an issue of energy and fuel choice, we have lost sight of how the basic materiality of our world literally rests upon the products of petroleum. These synthetic materials drove the postwar revolutions in productivity, labor-saving technologies, and massified consumption. Today, it is almost impossible to identify an area of life that has not been radically transformed by the presence of plastics and petrochemicals. These synthetic products have come to define the essential condition of life itself—they have become normalized as natural parts of our daily existence. This paradox must be fully confronted if we are to move beyond fossil fuels.

“The Chemical Century,” Fortune 41, no. 3 (March 1950): 116–121.

Vance Packard, The Waste Makers (New York: David McKay, 1960), 29.