On the Plasticity of Plastics

Carolyn L. Kane

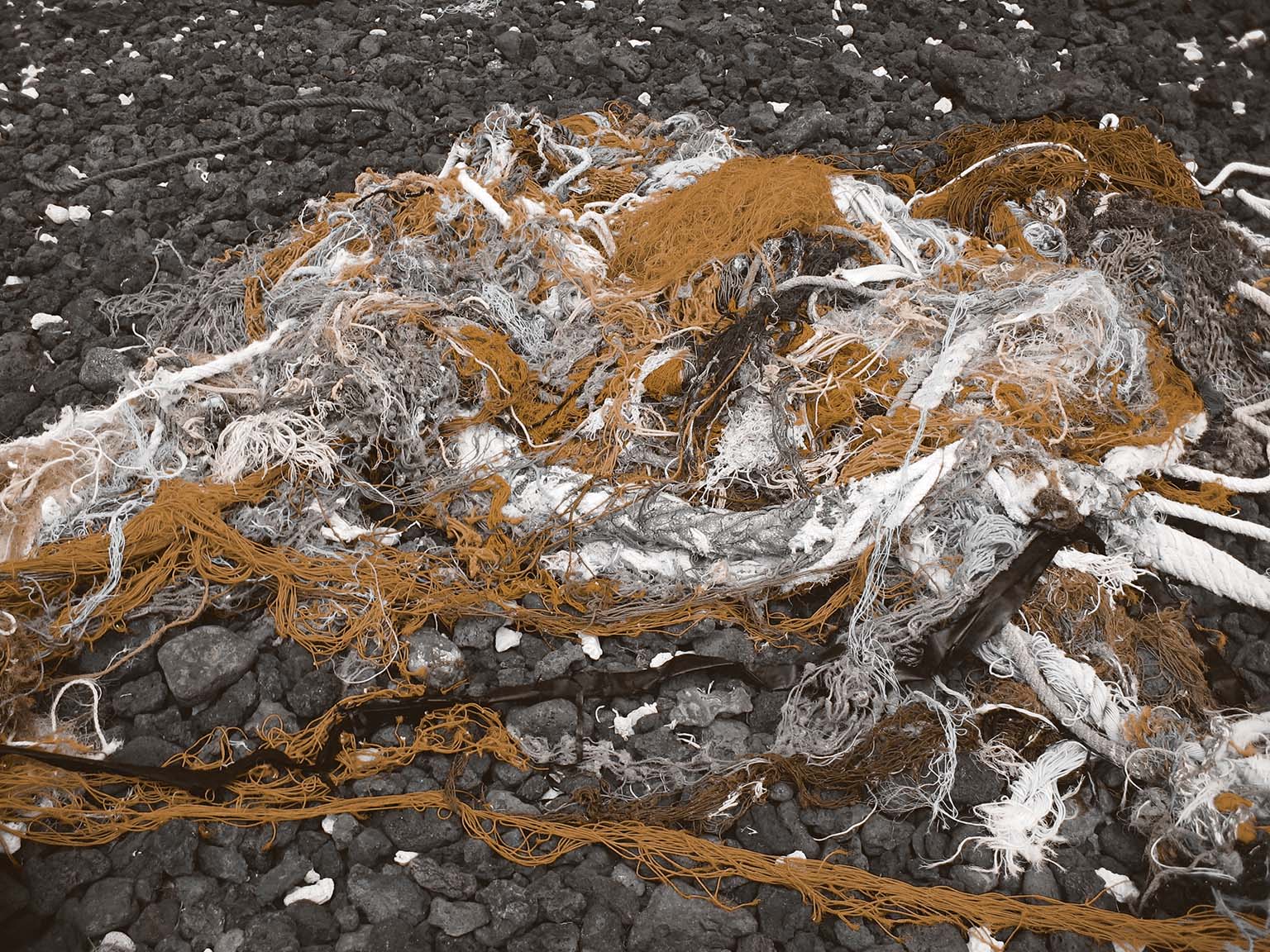

Ghost nets at Black Rock, Ka‘anapali Beach, Hawai‘i, August 2008. Photograph by Eric Johnson. Courtesy of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

The plastic configurations of our neural connections… are the forms of our identity. Plasticity, then, is the transcendental structure of our existential experience.

Catherine Malabou, 2022

No laboratory of the future is possible without the stuff of the past. The conditions of possibility for any “new” technology always derive from the present. Plastics are no exception.

Embraced by the Western world in the mid-twentieth century as something of a modern panacea, plastics promised to transform human nature and society through synthetic chemistry. Indeed, plastics have had enormous cultural, medical, and technological benefits, from electric wire insulation to vinyl blood bags for safe transfusions and light-emitting polymers for colored light in computing. And we might have failed to recognize just how radically they have reconfigured our everyday lives if they had not also come under the crosshairs of health and environmental advocates.

Critiques of plastic first emerged in the 1960s. Around the time pink flamingos and synthetic leather showed up on our lawns and our bodies, scientists began to link the so-called miraculous substance to acute environmental and health hazards. The research surmounted but, despite its findings and oppositions, the production and consumption of plastic has continued to scale, increasing almost twenty-fold in the last sixty years, with an annual production reaching 390 million metric tons in 2021.“Annual production of plastics worldwide from 1950 to 2021,” Statista Research Department, January 25, 2023, link. It is no longer a mystery where all this plastic goes: it ends up in our oceans, the same location that once supplied the fossil fuels to process natural gas, which, in turn, generated the byproducts used to develop plastics in the first place. Now these same oceans are haunted by our ghost gear, or “ghost nets,” plastics that do not biodegrade (polyurethane takes a thousand years to break down)—littered with toxic debris that traps, chokes, contaminates, and entangles ocean life. Each year, approximately one billion seabirds and mammals die from eating plastic bags.Murray R. Gregory, “Environmental Implications of Plastic Debris in Marine Settings— Entanglement, Ingestion, Smothering, Hangers-on, Hitch-hiking and Alien Invasions,” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences 364, no. 1526 (2009): 2013–2025; Martin Wagner, Magnus Engwall, and Henner Hollert, “(Micro) Plastics and the Environment,” Environmental Sciences Europe 26, no. 16 (2014): 16. Ghost gear not only evidences how plastic waste is disposed of in deadly ways but also, in its very status as lasting waste, structures plastic “neural nets” that bind our psyches to a future-past of unresolved trash. There is no escaping this ghost, but it can be a source of transformation.

When the ancient Greeks proposed a rigorous pursuit of “the good life,” the acquisition of endless streams of cheap plastic stuffs could not be further from what they had in mind. And yet, we have made the logic of consumption synonymous with “bettering” one’s self, family, and country. Spiritually motivated or not, it is what we do and work for. Artists, intellectuals, and many others have been critiquing our culture’s excessive consumption and plastic’s key role in it. And still, the belly of the beast grows stronger with each new consumer report.

How can we change the fate of plastic in the next millennium? Over the last two centuries, some innovations in recycling have enabled consumers in the Global North to yield more energy and power from less resources, causing fewer forms of direct biological and environmental destruction. But who is forgotten in this so-called global march to progress? In the service of a world-being for all—versus the postindustrial few—such questions must continually shape a truly progressive plastic laboratory of the future.

At the same time, a world-being in service of a future for all must start at home, with the individual’s capacity to function as a creative, generative being (homo faber), to transform the detritus of our personal psyches into a new home for a novel future. French philosopher Catherine Malabou suggests as much in her recent work on neuroplasticity, insisting past destructions can be resuscitated to form ourselves anew, “to fold oneself, to take the fold, not to give it.”Catherine Malabou, What Should We Do with Our Brain?, trans. Sebastian Rand (New York: Fordham University Press, 2008), 13; see also Catherine Malabou, Tyler Williams, and Ian James, Plasticity: The Promise of Explosion (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2022), 27, 164. Granted, Malabou did not have consumer plastics in mind, but she nonetheless invokes the uniqueness of plastic in its capacity—like humans—to give and receive fresh shape and form from the already wounded and traumatized in personal and collective registers. This is the material essence of plastics and it must remain the real matter of the future. How else can we recuperate plastic’s spiritual and ethereal fortitude, if not through its own plasticity?

“Annual production of plastics worldwide from 1950 to 2021,” Statista Research Department, January 25, 2023, link.

Murray R. Gregory, “Environmental Implications of Plastic Debris in Marine Settings— Entanglement, Ingestion, Smothering, Hangers-on, Hitch-hiking and Alien Invasions,” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences 364, no. 1526 (2009): 2013–2025; Martin Wagner, Magnus Engwall, and Henner Hollert, “(Micro) Plastics and the Environment,” Environmental Sciences Europe 26, no. 16 (2014): 16.

Catherine Malabou, What Should We Do with Our Brain?, trans. Sebastian Rand (New York: Fordham University Press, 2008), 13; see also Catherine Malabou, Tyler Williams, and Ian James, Plasticity: The Promise of Explosion (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2022), 27, 164.