Imperial Serial

Esther Leslie

“The World of Toys,” ICI Magazine 36, no. 266 (December 1958): 414–417.

“Arctic Junky: Plastic Sugar Puffs toy from 1958 washes up in the Arctic 59 years later to give a chilling warning about plastics in our ocean,” declared a 2017 headline in The Sun.Holly Christodoulou, “Arctic Junky,” The Sun, December 20, 2017, link. The miniature replica of the RMS Mauretania had bobbed 1,500 miles from Britain to Jan Mayen Island in the Arctic, from cereal box to gutter to dump, adrift in a sea for which it was never destined. “Ahoy! A Free Toy!” was the advertising tagline, and millions of children rummaged through cereal for this booty. However insignificant and throwaway its design, the material body of this giveaway has persisted, decaying only gradually, fading from pink to cream. In fact, it outlasted the original: the (roughly) 30,000-ton Cunard–White Star. A transatlantic ocean liner, built in Birkenhead and launched in 1938, which was scrapped at Thos. W. Ward’s shipbreaking yard in Fife in the mid-1960s.

Synthetic garments, like those made from Imperial Chemical Industry’s Terylene—the first 100-percent synthetic fiber invented in the UK—were sold on the promise of their durability, on their ability to keep shape. Yet, with each wash, their microfibers escape into water, into the world. Plastics drift and travel, depositing on the ground, in the sea, the air, and bodies. They have a way of finding their way back to where they came from (before they were plastic, before a thousand complex processes divided and recombined them)—to the sea where crude oil is siphoned, into the rocks where natural gas is extracted, or into the ground, concentrated in landfill, where they meet the now almost exhausted stocks of coal. Burned plastic waste reappears, like geological replicas, almost indistinguishable from stones and pebbles (“plastiglomerates” or “pyroplastics”) floating in the sea, washing up on beaches.See Madeleine Stone, “New Plastic Pollution Formed by Fire Looks like Rocks,” National Geographic, August 16, 2019, link; and Angus Chen, “Rocks Made of Plastic Found on Hawaiian Beach, Science, June 4, 2014, link. This, too, is a truth of plastic items—for, as much as they are durable, they are also cheap and made to be thrown away.

As the plastics disperse, so too does each item’s promise of a better life. Their bold colors, their resistance to the environment, to water, wind, and sun, their capacity to form anything and everything, by tricking nature or outwitting it—and holding all this for us forever—proves to be a lie. That they persist, even as they endlessly transform or shed themselves into the environment, becomes a problem in waiting.

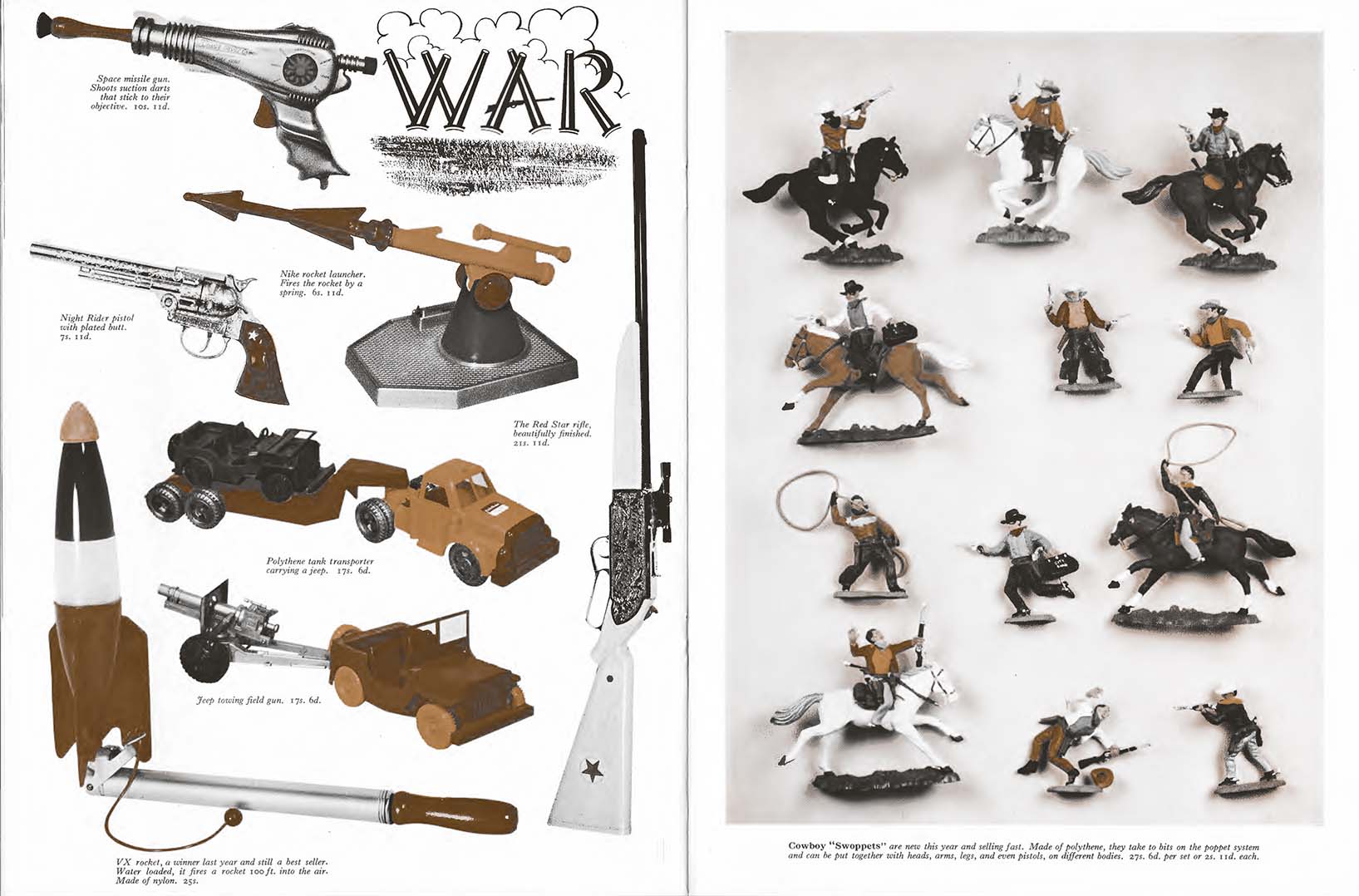

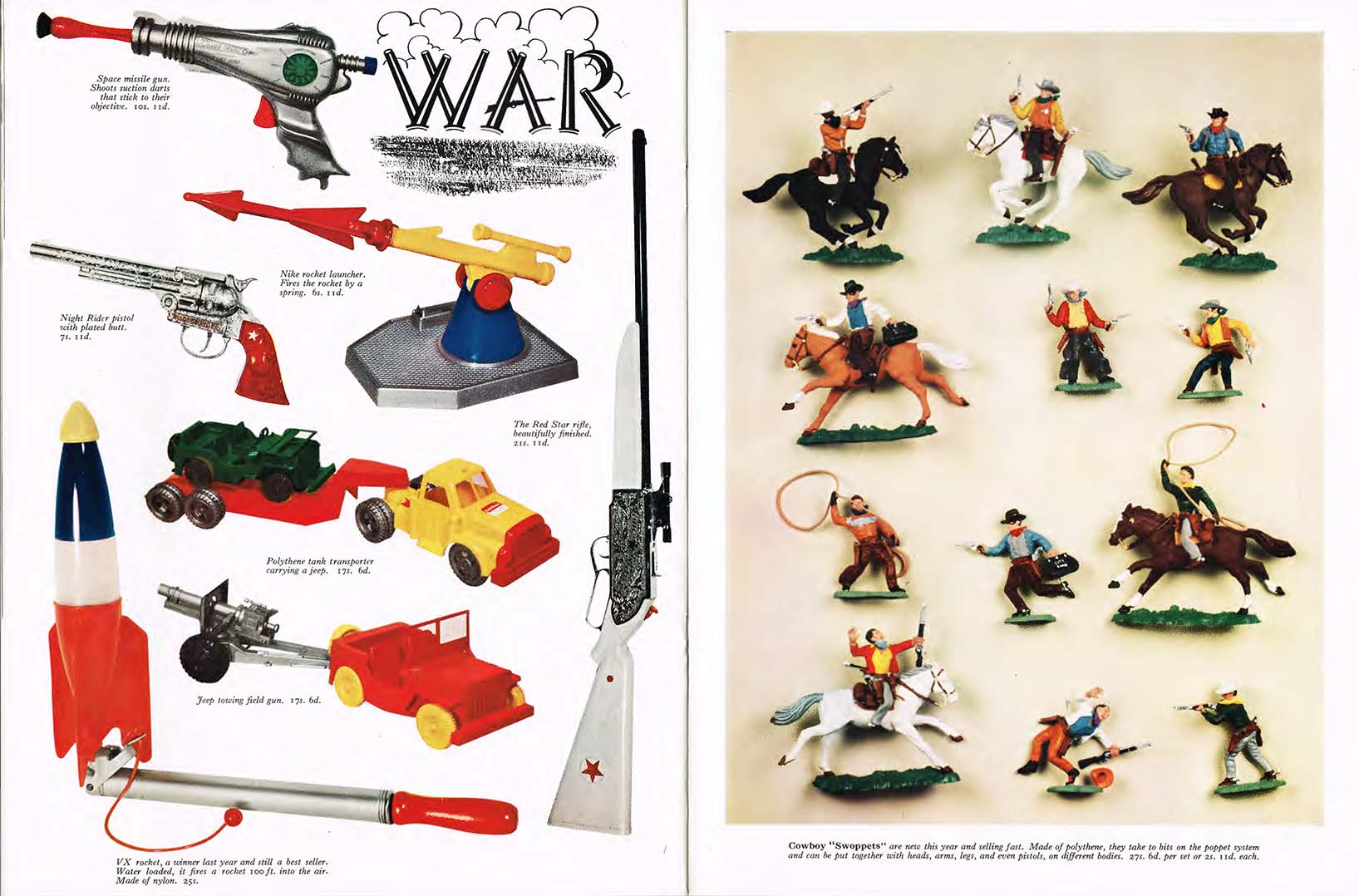

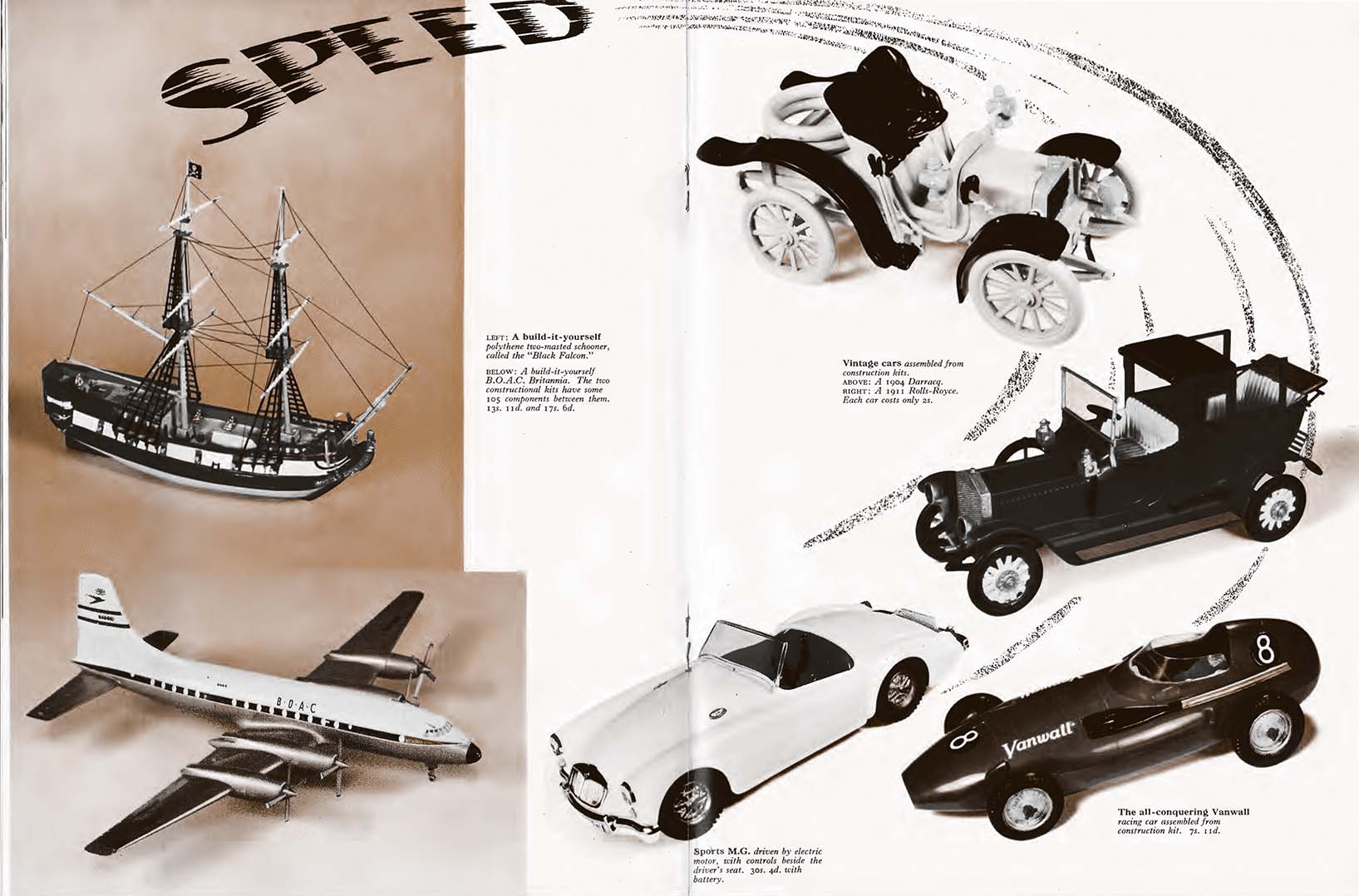

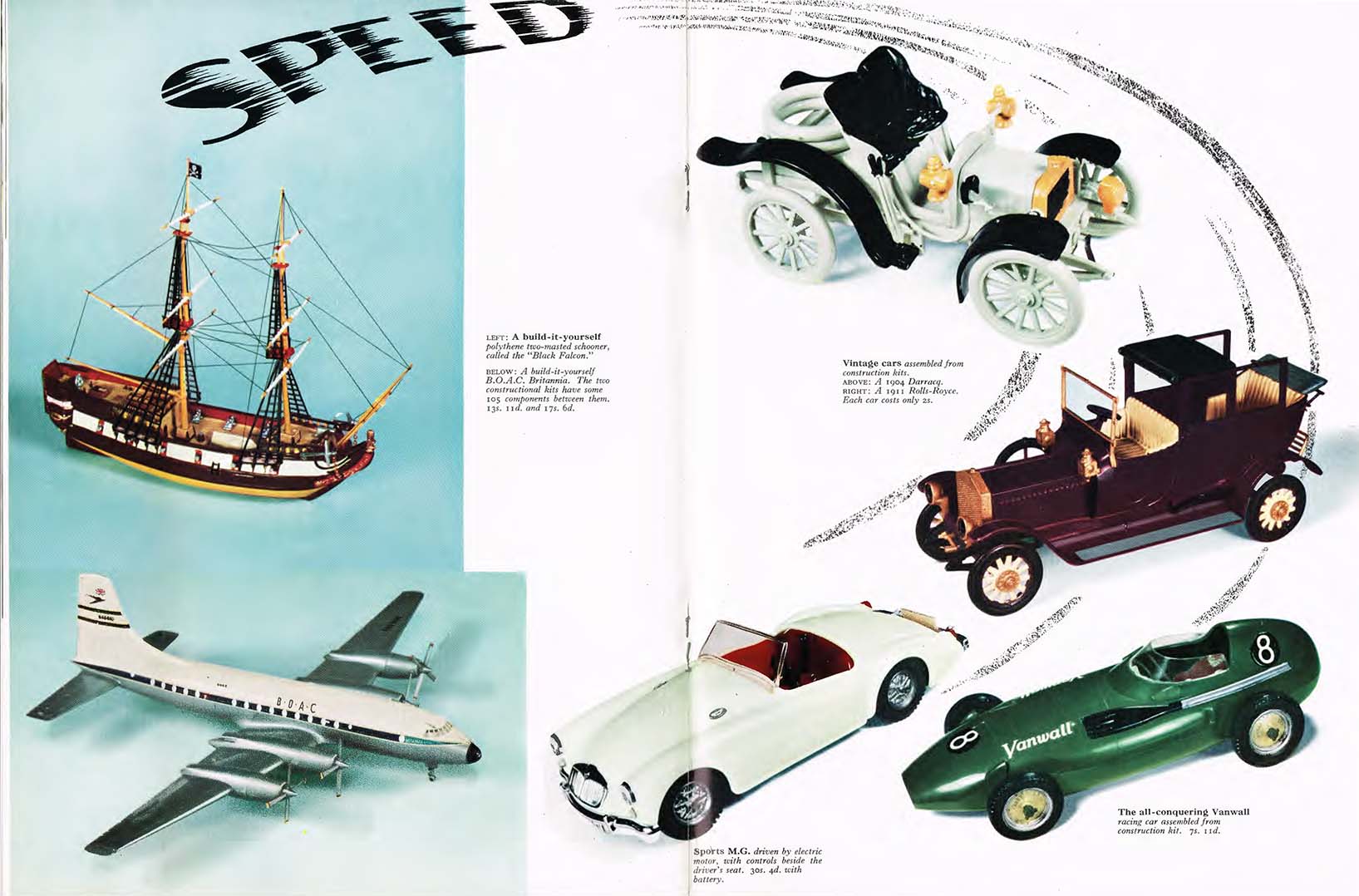

The December 1958 issue of Imperial Chemical Industry’s in-house magazine included a three-spread graphic titled “The World of Toys.”“The World of Toys,” ICI Magazine 36, no. 266 (December 1958): 414–417. Crowing about the competitive advantage of ICI’s plastic toys, which beat the historically dominant German toy industry, the feature revels in new playthings on the market. Rendered in miniature, in foam, nylon, and polythene, is a world of cowboys and wild animals, of war, of speed. A build-it-yourself polythene two-masted schooner called the “Black Falcon” sits next to a B.0.A.C. Britannia airplane. A Nike rocket launcher sits next to a space missile gun with darts that “stick to their objective.” Cheap, disposable toys do not disappear with childhood but rather persist, just like the imperial legacies they play at.

Holly Christodoulou, “Arctic Junky,” The Sun, December 20, 2017, link.

See Madeleine Stone, “New Plastic Pollution Formed by Fire Looks like Rocks,” National Geographic, August 16, 2019, link; and Angus Chen, “Rocks Made of Plastic Found on Hawaiian Beach, Science, June 4, 2014, link.

“The World of Toys,” ICI Magazine 36, no. 266 (December 1958): 414–417.