DuPont’s Better Living, Working Women, and Industrial Toxicology

Gabrielle Printz

“Energy output in ironing,” 1955. Photograph taken with a stroboscopic camera as part of a test at DuPont’s Haskell Labs. The test revealed that a woman ironing a shirt uses twice as much peak energy as a man does painting the living room ceiling. 1972341_3891, Series XIV, Box 12, Folder 2 “Studies of Industrial Fatigue.” DuPont Company Product Information photographs (Accession 1972.341), Audiovisual Collections and Digital Initiatives Department, Hagley Museum and Library, Wilmington, DE 19807.

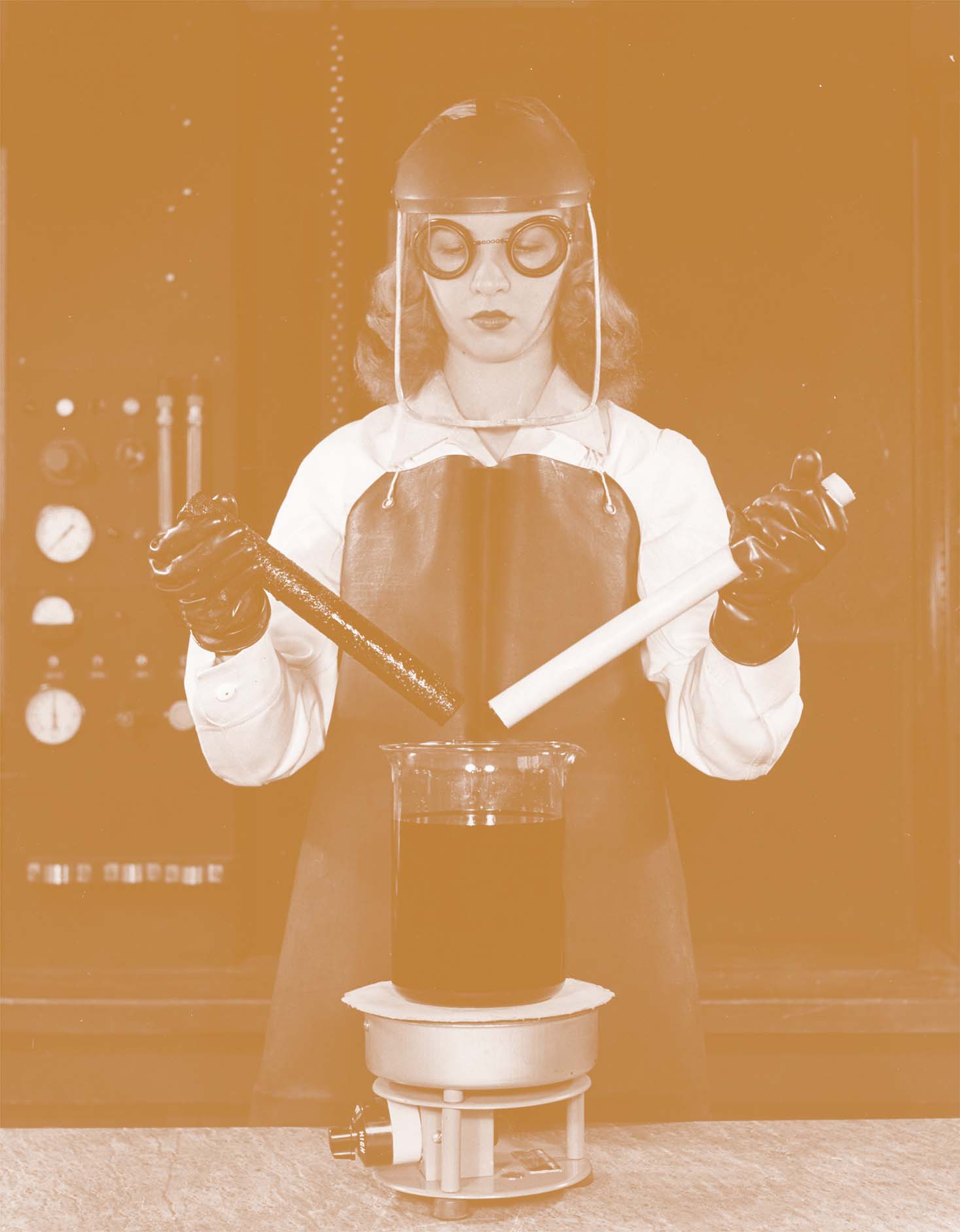

“Comparison of Teflon and plastic,” 1945. From a boiling bath of hot sulfuric acid, a laboratory technician lifts two rods of plastic. One has charred and deteriorated. The other, a rod of DuPont’s new Teflon tetrafluoroethylene resin, is not affected at all by the highly corrosive hot acid. 1972341_2498B, Series VIII, Box 8, Folder 10 “The creation of ‘Teflon’ at the Richmond, Virginia Plant.” DuPont Company Product Information photographs (Accession 1972.341), Audio- visual Collections and Digital Initiatives Department, Hagley Museum and Library, Wilmington, DE 19807.

It is 8:00 pm. My baby has just settled in his crib, and I am doing a bit of work. While he sleeps, I scroll the Hagley Library and Museum’s digital archives on my laptop from bed, while hooked up to two Medela breast pumps humming the silicone-softened song of mechanically expressed milk. Among my own tangle of tubing and power cords, I expand a black-and-white image of a woman operating an “electrically loaded” stationary bicycle in a temperature-controlled room.“Fatigue studies at the Haskell Laboratory for Toxicology and Industrial Medicine,” c.1950-1959, DuPont Company Product Information photographs (Accession 1972.341), Series XIV, Box 12, Folder 2 “Studies of Industrial Fatigue,” Audiovisual Collections and Digital Initiatives Department, Hagley Museum and Library, Wilmington, DE, link. She is outfitted in a sleeveless polyester set, a blood pressure cuff, and a thatch of nodes connecting her vitals to an adjoining room. The unnamed woman is a volunteer in a fatigue research study at the Haskell Laboratory for Toxicology and Industrial Medicine, the research institute established by the synthetics giant DuPont de Nemours, Inc. (DuPont) in 1935, initially to assess the occupational hazards of working in the pursuit of a “new world through chemistry.”“Haskell Laboratory for Toxicology and Industrial Medicine records 2739,” Finding Aid, December 11, 2022, Manuscripts and Archives Department, Hagley Museum and Library, Wilmington, DE, link. This was the company slogan that debuted in 1939 alongside an exhibition of its products—including a new artificial rubber called neoprene and a silk-like fiber called nylon—at the New York World’s Fair.“A New World Through Chemistry,” 1939, FILM_1995300_FC121, DuPont Company films and commercials (Accession 1995.300), Audiovisual Collections and Digital Initiatives Department, Hagley Museum and Library, Wilmington, DE, link. But the chemistry that wrought this new world was, by that time, already understood to be potentially volatile: a decade earlier, a concerning number of DuPont dye plant workers had been diagnosed with bladder cancer.

The Haskell Laboratory opened in the intervening years in response, facilitating internal research on its own products and manufacturing processes, professing its motivating concern to be worker safety. To that end, DuPont’s contribution to the twentieth-century pantheon of polymers was situated not only in petrochemical R&D but also the attendant field of toxicology. The creation of synthetics and the assessment of their unruly effects (or, in the company’s positive terms, their “safety”) would both be handled in controlled environments, separate from, but ever in relation to, the plant and the home.

Riding a bike, painting a ceiling, and ironing a shirt provided registers for manufacturing tasks in domestic labor. These activities have been recorded in stroboscopic photos which multiply the body performing already repetitive motions, and the archives of the Haskell laboratory are replete with images that depict women working.

Better Living

By the late 1940s, DuPont’s slogan exchanged the novelty of synthetic invention for one of convenient use. “Better living… through chemistry” tethered the good life to be had at home to the chemical enterprise with an ellipse (it reads to me now like an omission of relevant information rather than a dramatic pause). It referred to a lab-created and lab-maintained vision of a world of consumer goods: not only discrete objects, such as nylon stockings and grease-resistant neoprene gloves, but also coatings that integrated slick, non-stick, water-repellant, and unwrinklable surfaces into households and onto the bodies of American families.

The promise of “better living” was facilitated by DuPont’s own notion of polymerization: not just the technical process from which its proprietary materials sprung forth to constitute an entirely modern world of things but also the means by which that modern world could be engaged in its own self-reproduction through polymers. Plasticity was a social process: born in a lab, multiplied in a factory, and brought home by shoppers and factory line workers alike. Man-made and woman-worn, nylon, teflon, dacron, and other patented synthetics graced the bodies and the surfaces of everyday life, thus proliferating instances of exposure to them.

Forever Chemicals

DuPont’s polymers of non-transfer—resistant to ordinary messes and “indifferent to time,” as neoprene was introduced in 1939“A New World Through Chemistry.”—depended on the staying power of fluorocarbons, something Haskell was investigating as early as 1950.DuPont commercial featuring Haskell Laboratories,” 1950, FILM_1995300_FC12_02, DuPont Company films and commercials (Accession 1995.300), Audiovisual Collections and Digital Initiatives Department, Hagley Museum and Library, Wilmington, DE, link. In contemporary toxicology, these are PFAS (per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances) and “forever chemicals,” the bonds of which are very difficult to break down and thus remain persistent parts of our environment and ourselves.The “F” and “C” of “forever chemicals,” so named by the Harvard public health researcher Joseph Allen in a 2018 op-ed, refer to their component parts, fluorine and carbon; it’s less a play on words than a repackaging that he hoped would maintain concern about such toxins in the popular imaginary. See Joseph G. Allen, “Opinion: These Toxic Chemicals Are Everywhere—Even in Your Body. And They Won’t Ever Go Away,” Washington Post, January 2, 2018, link.

I’m only an amateur toxicologist, a specialization bred by the paranoia that accompanies new motherhood in the world of forever chemicals. I speak in millennial determinations of “that’s toxic” and in the syntax of “free from” to navigate the badness of the world I rely on to live and to make life. But my training is in history, so I bring this paranoia to the DuPont archives and to a short text that Roland Barthes wrote more than half a century ago. Reflecting on a 1953 exhibition of plastics in Paris, Barthes remarked on the material’s essential process of transformation—not plastic as object, but rather plasticity as an elemental force of production—as one that was conspicuously unpeopled: it was “nothing; nothing but a transit, hardly watched over by an attendant in a cloth cap, half-god, half-robot.”Roland Barthes, “Plastic,” in Mythologies, trans. Richard Howard and Annette Lavers (New York: Hill and Wang, 2013), 194–95. DuPont’s branding language is invoked in an article about the exhibition and its female spectators: “‘Do it by chemistry’ has now become a fashionable slogan in the feminine cir-cles of Paris.” In “French Impressed by Plastics Exhibit; Week’s Program of Chemical Salon Introduces Latest Developments to Women,” New York Times, July 11, 1953. DuPont showed a vision of plasticity that was necessarily human, contrary to Barthes’s observation. However, the idea of plastic as consisting in barely intelligible links—“nothing but a transit”—intuits something about the bodily thresholds that are only suggested by the TV parents and real life employees of DuPont’s “better living” media. While we are afforded glamor shots of artificial silk and microscopic images of mylar enhanced 25,000 times, what can’t be shown is the evidence of exposure to a volatile polymer or an indissoluble F-C bond. The hard-to-bind consequences of such repeated exposure might appear on medical charts years later, but, in the meantime, DuPont offered up pictures of people working toward that evidence, as professional observers or with their own bodies as research subjects.

The social and physical reproduction of life in plastics has largely been born by women, and certainly at this black-and-white moment of DuPont’s worldbuilding, when its fashioning of a new or better life was refracted through staid gender roles and corporate paternalism. The fatherly voice of mid-century advertising enunciated the convenience of its domestic products in the same breath as it assured houseworkers of the safety of synthetics in the home. Over footage of a mother at the sink with her small child, lathering her hands with a bar of soap (another DuPont offering), a gray-suited announcer effuses the importance of the “exhaustive tests” conducted by DuPont’s researchers. In a home office, he addresses the camera as a kind of disciplinarian: “You know, like people, chemicals are of many different types. Now most present no special problem. But some do require special care and treatment to make sure they behave properly and normally.”“DuPont commercial featuring Haskell Laboratories.” The camera shifts back to Haskell space, where caretaking is shown to proceed in the lab, as it does at home.

DuPont no longer produces PFAS, it professes on a dedicated page on its website and in a 2019 corporate commitment. But it hasn’t yet figured out how to decouple its processes from forever chemicals. The company, which has long pursued its own toxicology—for the products that still comprise and coat the world as we know it—instead leaves this decoupling up to people like me… a consumer, an academic, and a mother.

“Fatigue studies at the Haskell Laboratory for Toxicology and Industrial Medicine,” c.1950-1959, DuPont Company Product Information photographs (Accession 1972.341), Series XIV, Box 12, Folder 2 “Studies of Industrial Fatigue,” Audiovisual Collections and Digital Initiatives Department, Hagley Museum and Library, Wilmington, DE, link.

“Haskell Laboratory for Toxicology and Industrial Medicine records 2739,” Finding Aid, December 11, 2022, Manuscripts and Archives Department, Hagley Museum and Library, Wilmington, DE, link.

“A New World Through Chemistry,” 1939, FILM_1995300_FC121, DuPont Company films and commercials (Accession 1995.300), Audiovisual Collections and Digital Initiatives Department, Hagley Museum and Library, Wilmington, DE, link.

“A New World Through Chemistry.”

DuPont commercial featuring Haskell Laboratories,” 1950, FILM_1995300_FC12_02, DuPont Company films and commercials (Accession 1995.300), Audiovisual Collections and Digital Initiatives Department, Hagley Museum and Library, Wilmington, DE, link.

The “F” and “C” of “forever chemicals,” so named by the Harvard public health researcher Joseph Allen in a 2018 op-ed, refer to their component parts, fluorine and carbon; it’s less a play on words than a repackaging that he hoped would maintain concern about such toxins in the popular imaginary. See Joseph G. Allen, “Opinion: These Toxic Chemicals Are Everywhere—Even in Your Body. And They Won’t Ever Go Away,” Washington Post, January 2, 2018, link.

Roland Barthes, “Plastic,” in Mythologies, trans. Richard Howard and Annette Lavers (New York: Hill and Wang, 2013), 194–95. DuPont’s branding language is invoked in an article about the exhibition and its female spectators: “‘Do it by chemistry’ has now become a fashionable slogan in the feminine cir-cles of Paris.” In “French Impressed by Plastics Exhibit; Week’s Program of Chemical Salon Introduces Latest Developments to Women,” New York Times, July 11, 1953.

“DuPont commercial featuring Haskell Laboratories.”